On Sunday morning, March 18, 1945, under an unusually clear sky, the U.S. Eighth Air Force mounted one of its largest air raids against Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. The target was Berlin, capital of the Nazi regime. More than 1,300 heavy bombers from the Eighth Air Force, escorted by more than 600 fighter planes, departed their bases in East Anglia and flew eastward over the English Channel toward Germany. The payload that morning was more than 650 tons of 1,000-pound bombs.

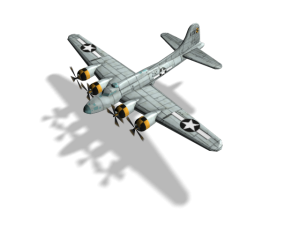

As a radio operator, Archie sat just behind the B-17’s bomb bay and in front of the waist section of the Flying Fortress. He was primarily responsible for assisting the navigator and communicating with other planes in the formation.

From RAF Thorpe Abbotts, Archie and the rest of the crew flew 13 to 17 missions without an incident, mostly in a B-17 named Heavenly Days. During their last fateful mission on March 18, 1945, they were manning a B-17G named Skyway Chariot (aircraft number 43-37521) because Heavenly Dayshad been damaged and was under repair.

The crew of Skyway Chariot that day had been together for many months and were “old hands” at the aerial warfare game. In addition to Archie, the crew consisted of pilot 1st Lt. Rollie C. King; co-pilot Lieutenant John S. “Jack” Williams; navigator Lieutenant John Spencer; nose gunner and bombardier Frank Gordon; flight engineer Ray E. Wilding; ball turret gunner Robert G. Mitchell; waist gunner Meyer Gitlin; and tail gunner James D. Baker. (A B-17 normally had two waist gunners, but on the March 18 mission, only one was assigned to Skyway Chariot.)

When on the offensive, the purpose of the combat box was simply the massed release of bombs over a target.

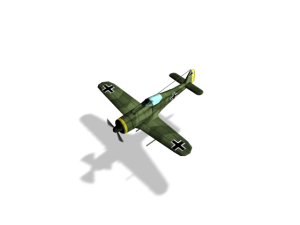

Bombing runs deep into Germany’s heartland could last eight hours or more and were typically met by heavy resistance from fighter planes and flak. Germany’s military pilots flew against the invading force in Messerschmitt Bf-109s, Focke-Wulf FW-190s and the new jet-powered Messerschmitt Me-262s.

As one would expect, the Me-262 was highly regarded by Germany’s Luftwaffe aces because it outclassed all other fighters of the period. It had a speed advantage, an excellent climb rate, and firepower consisting of four 30mm cannons in the nose.

By March 1945, almost all Allied air raids included at least 1,000 heavy bombers. During the March 18 bombing raid, a fierce defense was exhibited to protect Berlin, where Adolf Hitler and other Nazi elite were hunkered down.

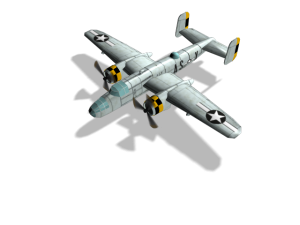

Before the bombers reached Berlin, Me-262s were scrambled to attack the B-17s and North American P-51 Mustang fighters escorting the Flying Fortresses. This would be the largest attack by Me-262 jets and piston-engine fighter planes against Allied bombers during the entire war.

Entering service near the end of the war, the faster and more powerful Me-262 Schwalbe(“Swallow”), was the most advanced fighter plane of World War II. It has been suggested that if the Me-262 had been introduced in greater numbers earlier in the war, it may have decisively impacted the outcome of many air battles in favor of Germany.

Just before reaching Berlin, the B-17s of the 100th BG encountered heavy bursts of flak from German 88mm and 105mm antiaircraft guns.

Then the antiaircraft guns went silent to allow swarms of deadly Luftwaffe fighter planes to do their work from close range. Thirty-seven fighter planes, including Me-262s, engaged the massive force of Flying Fortresses and escorting fighters. Luftwaffe pilots were determined to protect their capital from the enemy bombers. Tragically for the B-17s that day, this was also the first time in aerial combat that the Messerschmitts were also armed with the deadly R4M air-to-air missiles. According to eyewitnesses, the effect of the R4M rockets was devastating. Massive amounts of broken B-17 aircraft parts filled the crowded, smoky sky that day, creating havoc for the B-17s, as well as for the attacking German planes.

A second attack was fought off “halfway down the bomb run with no damage done. Since being hit, we were gradually trailing the formation and by the time we were over the target area, the rest of the formation was approximately one-half mile away.”

“As soon as we were hit––since there was no communication––I looked through the astrodome into the cockpit and I handed my toggalier his chute and then put on my own but still wasn’t sure to bail out, so I looked through the astrodome again and saw both the pilot and co-pilot preparing to abandon ship. Then looking at the right wing, which was burning pretty badly, I decided it was time to leave. I bailed out, floated to the ground, and was picked up [captured] immediately.”

Research reveals that Skyway Chariot was likely shot down by Oberleutnant (1st Lt.) Günther Wegmann flying an Me-262 from Jagdgeschwader 7 (JG7) Nowotny. Wegmann was an experienced Luftwaffe pilot credited with many aerial victories, including eight while flying his Me-262. Some of those kills included B-17s and P-51 Mustangs.They fired nearly 100 rockets into the midst of the bomber formation. Wegmann and Schnorrer each claimed two B-17s, and Seeler claimed one.

After the attack on Skyway Chariot, Oberleutnant Wegmann observed bits of aircraft, smoke, and flames. He started heading for home when he saw another bomber formation in his path, so he opened fire on it with his Mk 108 cannon. He was just over Glowen, Germany, when his jet fighter was hit by defensive fire from a B-17. His windshield and dashboard were badly smashed and after feeling a hard blow to his right leg he realized he had been shot; the wound was large enough for him to put his whole fist in. Oddly, he felt no pain.

His jet was still airworthy despite the damage, but soon flames erupted from one of his turbine engines, and he decided to bail out. He guided his Me-262 toward the town of Wittenberge, northwest of Berlin, which he recognized from the air, having flown over it many times. When the time felt right, he bailed out and engaged his parachute. He drifted past the town and landed in a meadow near a stand of pine trees.

An elderly German woman was the first to spot him, and he quickly identified himself as a German pilot. He was nervous because he was wearing a leather flight jacket obtained from a downed American flyer. If the villagers thought he was an American pilot, he might have been beaten or possibly killed. Instead, Wegmann was rushed away for medical treatment, and about four hours later his right leg was amputated.

After parachuting to earth, Archie and the five other surviving airmen were captured and imprisoned. He and the other crew members were transported to Stalag Luft I, a POW camp for American and British airmen at Barth in northeastern Germany.

The air war over Germany was incredibly costly. Casualties for the 100th Bomb Group are a perfect example. The “Bloody 100th,” so nicknamed because of the large number of losses it suffered, flew 306 missions during the war and lost 177 B-17 bombers to antiaircraft guns and Luftwaffe fighters; 765 airmen were killed while 903 were captured and interned at POW camps behind enemy lines or in neutral countries.

Figures differ, but one authoritative source says that the Eighth and Ninth U.S. Air Forces in Europe had a combined death toll of 24,963, including 510 who died of wounds and 537 declared dead. Inscribed on the Wall of the Missing at the American Military Cemetery, Cambridge, UK, are 5,127 names. More than 500 Eighth Air Force bombers and fighters were lost to antiaircraft fire, enemy aircraft, and “other causes.” It was a heavy price to pay for victory.

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/daily/deadly-duel-above-berlin/

Recent Comments